By Arnaud Darc

In July 2025, the United States confirmed a punitive 36% import tariff on goods from Cambodia, replacing an earlier proposed 49% rate. This move remains among the highest in a wave of new tariffs targeting export-driven economies and directly threatens Cambodia’s export engine – especially its garment, footwear, and travel goods sectors, which make up the vast majority of Cambodian shipments to the U.S.

The U.S. is Cambodia’s single largest market (accounting for ~38% of Cambodia’s exports in 2024, about $9.9 billion in value). A 36% tariff significantly raises the cost of Cambodian goods, rendering them less competitive almost overnight.

This report examines the updated impact of this tariff on Cambodia’s export competitiveness, with a focus on garments, and compares Cambodia with key regional competitors – Vietnam, Bangladesh, Myanmar, and Indonesia – across critical factors (labor costs, logistics, compliance, productivity, and trade incentives). We also assess implications for American consumers and the feasibility of shifting apparel production back to the United States.

Cambodia’s Export Profile and Tariff Shock

Cambodia’s growth over two decades has been fueled by export-oriented manufacturing, primarily of labor-intensive products. In 2024, Cambodian exports to the U.S. totaled roughly $10–12 billion, dominated by clothing, footwear, and travel goods. The garment industry alone employs around 800,000 Cambodians and supports millions of livelihoods indirectly. This success has relied on open access to foreign markets and tariff preferences (e.g. U.S. GSP benefits on travel goods, EU’s duty-free access).

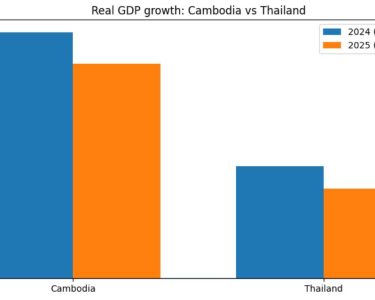

The revised 36% U.S. tariff represents a major external shock. In an industry with thin profit margins, such a tariff is still potentially ruinous – it renders Cambodian apparel more expensive than competitors’ products by a significant margin. Immediate impacts include: shrinking export orders, factory closures, and layoffs, with supply chain disruptions as U.S. buyers shift sourcing elsewhere. Analysts predict Cambodian exports to the U.S. could drop by over 40% in the first year, equating to a $4–7 billion loss. Hundreds of factories oriented to U.S. production face viability risks, with socioeconomic consequences for workers and the broader economy.

However, Cambodia’s pain would be competing countries’ gain. U.S. buyers pivot quickly in search of alternatives to Cambodia. Notably, other Asian suppliers like Vietnam and Bangladesh, which face slightly lower U.S. tariffs of 20% (with caveats for transshipment) and 35% respectively, are likely to absorb redirected orders. Indonesia, facing a 32% tariff, has also emerged as a formidable competitor. With its larger scale, diversified manufacturing base, improving logistics infrastructure, and political stability, Indonesia is increasingly attractive to international brands seeking to hedge risk across Southeast Asia. Countries not subject to such extreme tariffs – for example, African nations with duty-free access under AGOA – now enjoy a structural price advantage and could fill part of the sourcing gap. The next sections compare Cambodia’s competitiveness to Vietnam, Bangladesh, Myanmar, and Indonesia across key factors, to understand how a 36% tariff reshapes the sourcing equation.

Comparative Landscape: Cost, Capacity, and Credibility

Among Cambodia’s key competitors, labor cost and productivity dynamics vary widely. Bangladesh offers the lowest labor costs, with basic wages often half that of Cambodia’s, and its large-scale knitwear industry provides efficiency through volume, despite lingering concerns over compliance and logistics. Vietnam combines moderate wages with higher productivity, better infrastructure, and strong compliance capacity, making it a high-performing sourcing hub. Myanmar presents ultra-low wages but is burdened by political instability and reputational risk due to labor rights issues.

Indonesia, a rapidly rising competitor, offers a balanced mix: large-scale manufacturing, relatively stable governance, improving logistics, and wage levels similar to Cambodia. With a 32% tariff (versus Cambodia’s 36%), it now becomes a strong alternative for brands seeking to exit Cambodia.

In terms of logistics, Vietnam remains superior with modern deep-sea ports and fast shipping lanes. Bangladesh suffers from port congestion, while Cambodia lacks direct port access and often relies on overland shipping to Vietnam or Thailand. Indonesia’s logistics are improving, with government investments in port and customs reform.

On compliance, Cambodia has long been viewed as a leader in ethical manufacturing, supported by the Better Factories Cambodia initiative. However, Vietnam and Bangladesh have closed the gap with international audits and brand pressure, while Myanmar has largely fallen off sourcing maps due to human rights concerns.

Finally, market access matters. Cambodia’s reliance on MFN tariff rates without a trade agreement leaves it fully exposed. By contrast, African AGOA countries have zero-duty access to the U.S., and Vietnam has pursued FTAs to secure better market treatment. Cambodia’s policy vulnerability has now become a central competitive liability.

Geopolitical Undercurrent: Cambodia as Collateral Damage

While Cambodia is directly affected by the tariffs, it is crucial to recognize that it is not the primary target. The broader U.S. strategy is aimed at countering China’s influence, particularly by disrupting supply chains that pass through or rely on third countries for transshipment and market circumvention. Cambodia, with its increasing economic ties to China and role as a regional manufacturing node, has been caught in the crossfire.

This positions Cambodia not as a trade violator, but as collateral damage in a broader geopolitical confrontation between Washington and Beijing. The pressure is less about Cambodia’s trade policies per se and more about signaling to others — both allies and strategic competitors — that the U.S. will impose costs on any economy perceived to facilitate indirect Chinese market access. In this context, Cambodia’s tariff exposure is more about its strategic geography than its trade practices.

Understanding this dynamic is essential. If Cambodia’s status as a neutral or small economy does not shield it from such policies, then its long-term strategy must account for geopolitical alignment, not just economic efficiency. This means hedging dependencies, accelerating trade diversification, and engaging multilaterally with others in similar positions to reduce vulnerability in an increasingly polarized global trade environment.

Strategic Priorities and Non-Negotiables

In light of compressed timelines and structural constraints, Cambodia should concentrate on three non-negotiables:

1. EU trade pivot: Prioritize missions to Germany, France, and the Netherlands, capitalizing on EBA access and sustainability demand.

2. Textile ecosystem investment: Develop fabric, dyeing, and design capacities to enable full-package capabilities.

3. Logistics sovereignty: Expand Sihanoukville Port and cross-border infrastructure to reduce dependency on Vietnam and Thailand.

Institutional Execution Capacity

Cambodia must also address the issue of policy coordination. Without a dedicated, empowered task force spanning trade, industry, education, and finance, execution will lag behind strategy. Success will require a central authority with budget, mandate, and political backing to drive implementation across silos.

The implementation of a 36% U.S. tariff on Cambodian exports fundamentally alters Cambodia’s role in the global garment supply chain. Cambodia’s competitive position is severely weakened, as its primary exports (apparel, footwear, travel goods) become significantly more expensive for American buyers. Key regional rivals like Vietnam, Bangladesh, Indonesia, and Myanmar (and indeed others like African AGOA countries) stand to capture Cambodia’s lost market share, leveraging their lower tariffs, lower labor costs, or trade privileges. Cambodia transitions from a cost-competitive supplier to one of the least favorable sourcing origins in the U.S. market.

The analysis shows that labor cost advantages in Cambodia (or any efficiency and compliance strengths it had) are wiped out by the tariff handicap. Buyers will shift to Bangladesh, Vietnam, or Indonesia where possible, despite any slightly longer shipping times or compliance concerns, because those alternatives are simply much cheaper after tariffs. Even countries that were previously marginal players can become significant if they have tariff-free access – we may see a boost for apparel industries in countries like Kenya, Madagascar, or Honduras as a result. Cambodia, on the other hand, faces an existential threat to its manufacturing sector unless it can pivot to other markets or upskill into products less sensitive to cost (a challenging proposition).

For American consumers, the 36% Cambodia tariff (as part of a broader tariff package) likely means higher prices for apparel and footwear, with estimates projecting billions of dollars in added costs to the U.S. economy. In exchange, there is only a limited prospect of jobs returning to the U.S. garment sector. The comparative cost breakdown makes clear that re-shoring en masse would lead to much higher retail prices – something U.S. consumers and retailers have historically been unwilling to bear. Thus, the more probable outcome is trade diversion: sourcing will recalibrate away from Cambodia (and any other highly tariffed countries) toward those with lower tariffs or existing trade agreements. We are likely to see Vietnam, Bangladesh, Indonesia, and others increase their U.S. export share, while Cambodia’s export earnings plunge, with painful impacts on its economy and workers.

In essence, the 36% tariff on Cambodia achieves the opposite of “bringing jobs back” in the apparel industry – it redistributes jobs from one poor country to other countries, rather than to the U.S. The Cambodian case underscores a classic lesson of economics: when faced with a sudden cost spike (like a tariff), global supply chains will adjust to the next cheapest configuration. Cambodia loses competitiveness, Vietnam, Bangladesh, and Indonesia regain it (to a lesser degree Myanmar, given its issues), and American consumers pay somewhat more regardless. Unless the tariff is lifted, Cambodia’s position as a garment supplier to the U.S. will remain deeply uncompetitive, forcing a painful transition. Meanwhile, the U.S. apparel market will continue to be supplied predominantly by imports – just sourced from locations that avoid the heaviest tariffs – and the intended renaissance of American-made clothing will, in reality, be limited. The policy may therefore be more effective as a protectionist symbol than as a practical creator of U.S. manufacturing jobs, while its damage to a vulnerable developing economy like Cambodia is very real and severe.

By Arnaud Darc; Co-Chair, Government–Private Sector Forum, Working Group D and CEO of Thalias Co., Ltd.