David Van

There is a truth many people in Cambodia recognize, yet few are willing to say out loud.

It does not appear in policy papers or official speeches. It is rarely acknowledged in public forums. Yet it quietly shapes decisions, delays progress, and defines the limits of reform.

That truth is this: one of Cambodia’s greatest obstacles to meaningful transformation is not a lack of ideas, resources, or talent—but a deeply entrenched culture of rent-seeking that has become normalized within the system.

This is not the crude image of corruption that people often imagine. It is far more subtle, and far more damaging. It is the quiet expectation that nothing moves without someone’s “involvement.” The unspoken rule that every process must pass through certain hands. The belief that influence, rather than efficiency, is the true currency of progress.

Simply “How Things Work.”

Over time, this mindset has become so embedded that it no longer appears abnormal. It is simply “how things work.”

And that is precisely the problem.

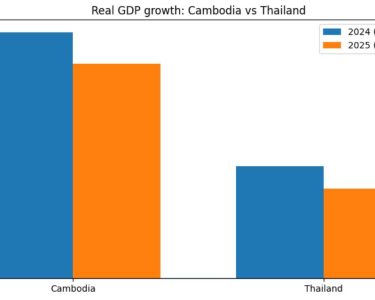

Read More: Opinion – Economic Velocity and the Real Contest Between Cambodia and Thailand

In such an environment, systems exist not to function independently, but to reinforce personal relevance. Decisions are delayed not because they are complex, but because delay itself has become a form of power. Projects stall not due to lack of merit, but because too many actors must be seen to play a role.

The result is a culture where indispensability is rewarded more than effectiveness.

This does not only slow development—it reshapes behavior. Capable professionals learn that initiative can be risky. Innovation becomes something to manage carefully, not encourage. Over time, ambition gives way to caution, and creativity to compliance.

What emerges is a paradox: a country with abundant talent and ambition, yet constrained by systems that quietly discourage both.

This is not a uniquely Cambodian problem. Many countries that emerged from periods of conflict or instability faced similar challenges. When institutions are weak, personal networks fill the vacuum. Over time, those networks harden into informal power structures that resist reform—not necessarily out of malice, but out of self-preservation.

Yet what may have once served as a survival mechanism becomes, in a more stable era, a liability.

The real cost of this dynamic is not just inefficiency. It is the erosion of trust. Investors hesitate when outcomes depend more on relationships than rules. Professionals lose motivation when merit is secondary to proximity. Citizens disengage when systems feel opaque and unresponsive.

Gradually, the gap between policy and practice widens. Strategies look impressive on paper but struggle in implementation. Reform becomes performative rather than transformative.

And this is where the danger lies.

Delayed Approvals, Diluted Reforms, and The Normalization Of Mediocrity

Because a nation does not stagnate suddenly. It stagnates quietly—through delayed approvals, diluted reforms, and the normalization of mediocrity. By the time the consequences become visible, momentum has already been lost.

Cambodia today stands at a critical juncture. The country has achieved remarkable resilience, recovering from periods of profound hardship and positioning itself as a growing economy in a competitive region. But resilience alone is no longer enough. The next phase of development demands a different kind of courage.

It requires the courage to confront internal habits that no longer serve the national interest. To move from a culture of gatekeeping to one of facilitation. From systems built around personalities to systems built around principles.

This does not mean dismantling institutions or undermining authority. On the contrary, it means strengthening them—by making them predictable, transparent, and capable of functioning regardless of who occupies a particular office.

Real reform is not loud. It does not announce itself with slogans or task forces. It happens quietly, through redesigned processes, clearer accountability, and the willingness to let go of unnecessary control.

Above all, it requires an honest acknowledgment that some of the obstacles to progress are self-created.

Cambodia has shown extraordinary resilience in the face of adversity. It has rebuilt cities, restored stability, and reclaimed its place in the region. The question now is whether it can take the more difficult step: confronting the internal habits that hold it back.

The elephant in the room is no longer hidden. It is standing in plain sight.

The choice ahead is not about whether Cambodia can grow. It is about whether it is willing to let go of the very practices that prevent it from becoming what it has the potential to be.

David VAN

1-1-2026

David Van is an experienced and savvy business and policy advisor. He is adept in Government Relations Advisory Services, Blended Finance and PPP Conceptualization with four decades of experience with international firms in regional senior management roles and the development world in South-East Asia. He is Multi-Sectoral, Multicultural and multilingual fluent in English, Cambodian, French and Chinese.