Nith Kosal

New tariffs imposed by the United States and renewed border conflict with Thailand have put Cambodia under fresh economic pressure. For a country long dependent on exports, foreign direct investment, and imports to meet domestic needs, these shocks expose vulnerabilities in its growth model. If Cambodia wants to accelerate economic and social development – and become more self-reliant – it must make a bold choice: introduce progressive taxation to expand fiscal space for public investment and build a sustainable future.

Fiscal constraints challenge the development of Cambodia’s social welfare, education, and healthcare systems – the foundations of long-term economic prosperity. Cambodia has indeed made remarkable strides over the past three decades, cutting the poverty rate from nearly 59% in 1993–94 to 17.8% by 2019–20. But this progress is fragile. Research shows that many households that have escaped poverty remain vulnerable to falling back into it when faced with shocks such as economic downturns, pandemics, or climate disasters. During the pandemic alone, roughly 460,000 people slipped back into poverty, pushing the national poverty rate up by nearly three percentage points.

Poverty leads to social problems. In Cambodia, it has led to high school dropout rates, especially at the upper secondary level. Although 90% of children were enrolled in primary school in 2019, only 47% were enrolled in lower secondary and 31% in upper secondary. Enrollment in higher education stands at only 18% as of 2023. While the average life expectancy reached 71 years in 2023, about 60,000 deaths annually are caused by noncommunicable diseases, a major challenge for the health system.

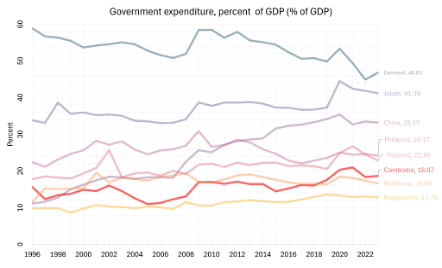

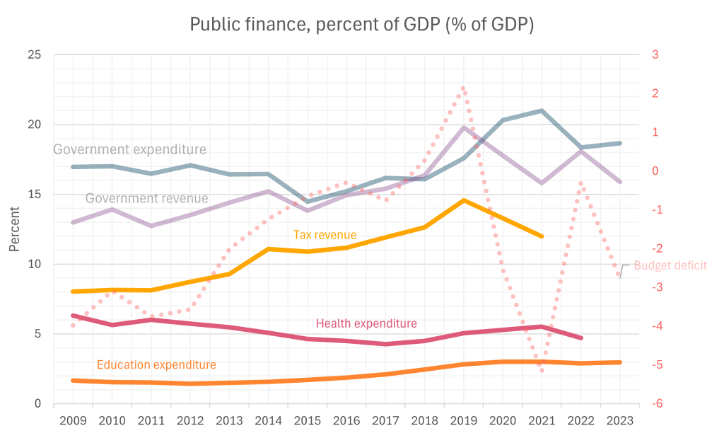

More funding could make a crucial difference. Education and healthcare have improved greatly since 2009, when the government allocated a significant share of its budget, between 2% and 5% of GDP annually, to these sectors. Still, these sectors remain underfunded and urgently need more resources.

The Question Is: Where Will The Money Come From?

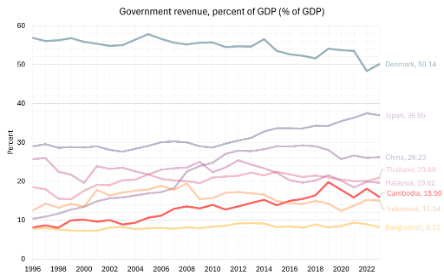

Money comes from taxes. In 2024, the General Department of Taxation (GDT) collected revenue equal to about 14.57% of its GDP. While the government aims to increase tax revenue, the current tax structure remains narrow and heavily reliant on indirect taxes, particularly value-added tax (VAT), import duties, and corporate income tax. There is still room for Cambodia to increase tax collection.

Progressive taxation offers more than a means to raise government revenue – it’s a powerful tool to reduce inequality and foster inclusive growth. The top 1% of Cambodians take home 18.1% of the national income, and the top 10% receive 45.2%, according to the 2023 World Inequality Database. In terms of wealth, the disparity is even more stark: the top 1% of the population own 25.3% of the country’s wealth, and the top 10%, less than 1.7 million people, hold nearly 60%. The remaining 16 million people share just 40.2% of all wealth. Although inequality has declined overall since the Global Financial Crisis, the gap between the wealthiest and the rest remains dramatic. The bottom half of the population receives only 14.5% of the total national income and holds a mere 4% of the wealth.

This concentration of wealth fuels the dominance of large business groups that enjoy high market concentration. Such dominance creates barriers for smaller enterprises, limiting their growth and ability to compete. Taxing the wealthy would help reduce their unchecked market power, slow excessive investment concentration, and redirect resources into public investment programs that can stimulate sustainable GDP growth.

Taxation of the rich is a legitimate form of domestic resource mobilization, widely practised worldwide: 151 out of 195 countries have adopted some form of progressive tax. Cambodia must follow suit without delay.

To start, Cambodia should focus on four types of progressive taxes: capital gains tax, personal income tax, net wealth tax, and unrealized capital gains tax.

Capital gains tax is the tax that applies to profits earned when individuals or firms sell, transfer, or dispose of assets at a higher price than their purchase cost. The government plans to implement this tax by the end of 2025. It will cover assets like property, leases, shares, goodwill, intellectual property, and foreign currency, with a tax rate of 20%. If implemented as planned, this policy will mark a major step forward.

Personal income tax is levied on individual earnings such as wages and salaries. Cambodia does not have this tax but does have a monthly salary tax, collected by employers, with rates from zero up to 20% depending on income level. The current system excludes those in the informal sector, which accounts for 88.3% of workers, and the top tax rate is low for high-income earners. Expanding this system to include all earners and raising the top rate from 20% to 35% for those earning more than $5,000 per month would be a significant step toward fairness and revenue expansion.

Next, a net wealth tax – an annual tax based on the total value of an individual’s or household’s assets minus liabilities – could provide an important revenue stream. Though complex to administer, countries like Spain offer a good model, applying progressive rates ranging from zero to 1.5%. No tax is charged on wealth below $50,000, but rates increase to 0.5% for wealth between $500,001 and $1 million, 1% for $1 to $2 million, and 1.5% for assets exceeding $2 million. Cambodia could adopt a similar system, tailored to local conditions, targeting the top tier of wealth holders.

Finally, Cambodia should consider piloting an unrealized capital gains tax, which taxes the increase in value of assets that owners have not yet sold. For example, if an individual purchased shares for $2 million and real estate for $3 million in 2023, and these assets rose to $3 and $5 million, respectively, by 2024, the tax would apply to the $3 million unrealized gain, according to the law’s tax rate. Although few countries apply such a tax due to its complexity, piloting it for select asset classes or income groups, starting with the top 1%, could be feasible and effective. This type of tax could significantly contribute to reducing wealth inequality.

Why These Taxes are Being Introduced

To design and implement new taxes, the authorities must first earn public trust. They should provide clear information about why these taxes are being introduced, how the revenue will be used, and what taxpayers can expect in return. Citizens need to understand who will pay more, who will pay less, and what improvements they can expect to see. The government must communicate this with a strong emphasis on its long-term vision and explain how changes will be made step by step from new revenue.

GDT, with its Special Tax Audit Unit and technical teams, should collaborate with other government agencies and financial institutions, both local and international, to identify and register the top 10% of income and wealth holders in Cambodia. This mapping exercise is essential to determine potential taxpayers and build a reliable income and asset data infrastructure. A national asset registry, serving as a digital platform for tracking and reporting income and wealth, would enhance transparency and enforcement capacity.

The government can then roll out reforms step by step. Phase one, in 2026, should implement the capital gains tax as planned, laying the foundation for tax reform that will mobilise resources to promote inclusive growth. Phase two, in 2028, should transform the salary income tax into a comprehensive personal income tax. Phase three, in 2030, would pilot a net wealth tax targeting the top 1%. Finally, phase four, in 2032, would introduce an unrealized capital gains tax on the top 1%.

Cambodia must act now to increase public investment and mobilize domestic resources by taxing the wealthy, who hold half of the nation’s wealth. Further delay risks locking the country into a cycle of stagnation, where local businesses struggle to grow, workers remain under-skilled, and public health and education deteriorate.

Note: Kosal Nith is a Research Fellow at the Future Forum, a public policy think tank based in Phnom Penh. This article was written as part of the Future Forum’s Inclusive Policy Fellowship, an endeavour supported by the Australian Government through The Asia Foundation’s Ponlok Chomnes II: Data and Dialogue for Development in Cambodia. This article was first published in CamboJa.